The combination of the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 and the focus on ending the Vietnam War, starting in 1965, took the momentum out of SANE and the nuclear test ban movement. But in the 1980s, the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign reinvigorated the fight. (Kleidman, 1993, pp. 121-124).

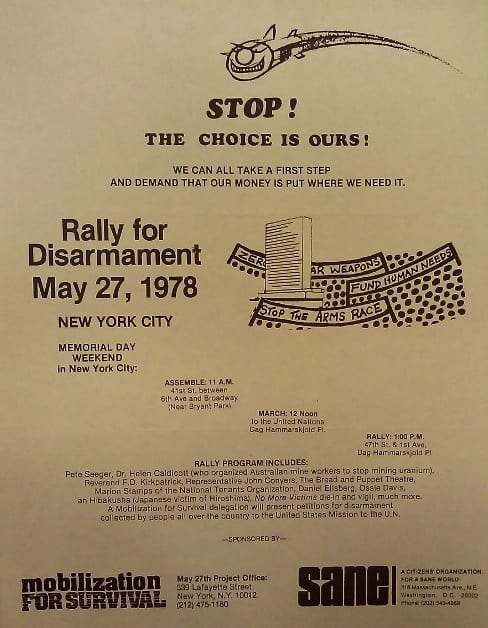

In the late 1970s, local groups began organizing around opposition to nuclear power plants. After the 1979 accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant and the 1980 leak at the Indian Point nuclear power plant, environmentalists and peace activists saw that they could work together toward the same goals. A successful rally for disarmament at the UN’s First Special Session on Disarmament in May 1978 showed activists that there still was interest in demonstrating for disarmament.

Flyer for May 27, 1978 disarmament rally (Printed Ephemera Collection on Organizations, PE 036, Box 73, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archive)

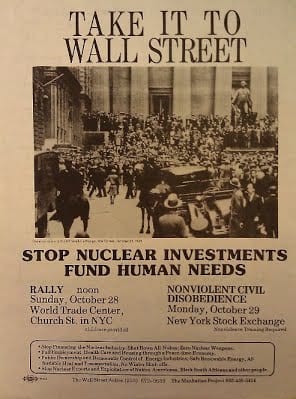

Another rally took place in New York City on Wall Street in 1979; the anniversary of the 1929 Stock Market Crash was marked by a demonstration that blamed corporations for funding the arms race. It was organized by a group called “The Manhattan Project.” (New York Times, 1978; Kleidman, 1993, p. 137; New York Times, 1980).

Flyer for Manhattan Project’s “Take it to Wall Street” Rally and Action, 1979

(Manhattan Project Collection, 1979, CDG-A, Peace Collection, Swarthmore College)

These events combined with a rightward shift in national politics made it the time for a resurgence of nuclear–focused peace activism. In November 1980, Ronald Reagan, who promised to increase military spending, was elected president, while 59 towns in Massachusetts passed local referenda supporting a nuclear freeze. After this the nuclear freeze movement grew rapidly, becoming one of the largest peace movements in US history. (Kleidman, 1993, pp. 144-145).

The UN’s Second Special Session on Disarmament on June 12, 1982 was greeted in New York City by 750,000 to 1 million protesters. The month before, President Reagan announced that he would negotiate a new arms control treaty: START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), but groups like SANE and Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign did not think it went far enough. The June 12 rally on the Great Lawn of Central Park showed just how many people agreed. (Katz, 1986, pp. 150-151; Kleidman, 1993, p. 154).

Internal organizational problems and Reagan’s reelection in 1984 slowed the Nuclear Freeze movement’s momentum. Only 60,000 demonstrators showed up in New York for the UN’s Third Special Session on Disarmament in 1988. (Kleidman, 1993, pp. 161-163; Lueck, 1988).

Nevertheless, the ideas expressed by the resurgent campaign had an impact on New York politics, as the City Council passed resolutions supporting its primary aims. In 1979, the Council called on the US President to seek ways to end the arms race and in the early 1980s called on both the USA and USSR to adopt a “Mutual freeze on the testing and production of nuclear weapons.” In 1983, the city declared itself a Nuclear Weapons-Free Zone.

Back to NYC Nuclear Archive Home

Next Page: Nuclear Power and Its Discontents

By Catherine Falzone, 2012. Adapted from Nuclear New York archive with permission.