Just as important to the story of “Nuclear New York” are the things that did not happen. New York was never attacked with nuclear weapons, but writers and artists speculated wildly about what might happen to New York in a nuclear attack, or used the city as a dramatic example of the devastation a bomb could wreak on a highly populated area. While these particular speculations did not come to pass, they were sadly correct in their visions of New York as a target.

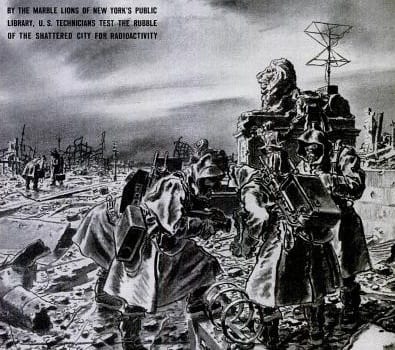

Three months after the atomic bomb was used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Life ran a story called “The 36-Hour War” in which they imagine that the US has been attacked by nuclear weapons. In their scenario, 40 million people die, but the US still wins the “36-hour war.” But New York is in ruins. The only structure left standing is one of the lions in front of the New York Public Library.

A lonely lion in the midst of nuclear destruction.

(Noel Sickles art from “The 36-Hour War,” Life, November 19, 1945, 35.)

An 1947 article in Reader’s Digest, “Mist of Death over New York,” vividly describes an atomic attack on New York and its aftermath. 389,101 people die, including some who were killed by the National Guard or in the crush of people trying to escape the city. (Boyer, 1994, p. 67).

A particularly chilling account comes from Cornell physicist Philip Morrison, who had been one of the first Americans to inspect Hiroshima. His piece in the compilation One World or None, “If the Bomb Gets Out of Hand,” describes an atomic bomb falling on 3rd Ave. and E. 20th St.:

From the river west to Seventh Avenue and from south of Union Square to the middle Thirties, the streets were filled with dead and dying. The old men sitting on the park benches in the square never knew what had happened. They were chiefly black on the side toward the bomb. Everywhere in this whole district were men with burning clothing, women with terrible red and blackened burns, and dead children caught while hurrying home to lunch (in Boyer, 1994, pp. 77-79).

A less graphic but still frightening example comes from the 1964 film Fail-Safe, directed by Sidney Lumet, in which a technical failure causes US bombers to carry out orders to bomb Moscow. Unable to call the bombers when they move past their “fail-safe” points, the President of the United States (Henry Fonda) bargains with the Chairman of the USSR. In a quid pro quo, the two decide that if Moscow is hit, the President will order an attack on New York City. At the end of the movie, a bomb is dropped on Moscow. The last scene is the bombing of New York.

In 2011, the academics Robert Jacobs and Mick Broderick curated an exhibition of cultural representations of nuclear attacks on the city, called Nuke York, New York, at Cornell University’s Hartell Gallery. In an article reflecting on the persistence of such imagery, and its revival after 9/11, they wrote:

It is clear from the diversity and longevity of these cultural manifestations, both state sanctioned and independent, that an “American Hiroshima” emphasizing New York City as the locus for an “inevitable” nuclear attack has penetrated deep into the American psyche. (Jacobs & Broderick, 2012).

Nuclear New York imagery in the 2006 video game Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Double Agent (Jacobs & Broderick, 2012).

Back to NYC Nuclear Archive Home

By Catherine Falzone and Matthew Bolton, 2018. Adapted from Nuclear New York archive with permission.