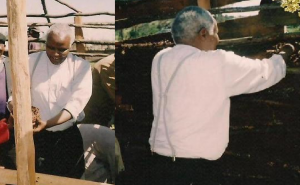

Bishop Korir helps a family rebuild their house after the post-election violence of 2007/2008.

It is with great sadness that the International Disarmament Institute has learned of the passing of a dear friend and partner, Bishop Cornelius Korir of the Catholic Diocese of Eldoret in Kenya. At great risk to himself, Bishop Korir intervened personally to address violence in the North Rift region of Kenya, notably in conflict following elections in 1992, 1997 and 2007/2008. He was known to step between groups of fighters, mobilize care for wounded people, build connections across lines of hostility and encourage antagonists to seek healing and reconciliation.

“We wish to offer our deepest condolences to the family, colleagues and friends of Bishop Korir, as well as the Diocese of Eldoret,” said Dr. Matthew Bolton, Director of the International Disarmament Institute. “He was a courageous witness for peace, social justice and reconciliation in Kenya, but his voice also resonated far beyond East Africa, inspiring many of us around the world to work for peace at the grassroots level.”

Following the 2007 elections, as the North Rift region became engulfed in violence, some 10,000 people flocked to the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Eldoret. Bishop Korir made the cathedral’s grounds a sanctuary for displaced people, persuading those with guns to respect the sanctity of the Diocesan property and mobilizing the provision of aid to those camped there.

Following the 2007 elections, as the North Rift region became engulfed in violence, some 10,000 people flocked to the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Eldoret. Bishop Korir made the cathedral’s grounds a sanctuary for displaced people, persuading those with guns to respect the sanctity of the Diocesan property and mobilizing the provision of aid to those camped there.

In the aftermath, he and his Diocesan priests, nuns and lay staff facilitated crosslines conversations, establishing Peace Committees of local people who discussed how to calm the conflict and address underlying, long-lasting colonial legacies such as land disputes, the construction of exclusive ethnic identities and corruption. In 2009, supported by Catholic Relief Services and Caritas Australia, he published a book about his experiences, outlining his method of Amani Mashinani (Peace at the Grassroots):

One of our early initiatives was to hold peace seminars and trainings at hotels and our pastoral center, as an attempt to bring people to a neutral and convenient location. … However, we began to realize that the same people kept coming to all our seminars. … We were contributing to the creation of a class of ‘professional seminar goers’ …. We had unwisely and mistakenly relied on these people to carry the message of peace to the gun-wielders who caused violence…. But this was not effective…. We realized we needed to start again at the grassroots, to reach the actual perpetrators and victims of violence. We needed to facilitate amani mashinani – peace in the village, not peace in urban hotels. Sustainable peace would have to be rooted in the local environment and engage those most affected by the violence, not just those who show up to NGO conferences.

Recently, Pace University’s International Disarmament Institute partnered with the Catholic Diocese of Eldoret to develop a follow-up book, Mardhiano Mashinani (Reconciliation at the Grassroots). With co-authors from the Diocese and beyond, Korir explored how reconciliation after violent conflict is a subtle, slow and often difficult process that is not just about ending observable fighting. Drawing on almost 25 years of experience with peacebuilding at the community level, Korir argued that reconciliation requires communities to recognize the worth of others, atone for injustice, heal wounds of the spirit and commit to building a non-violent, equitable and just society. While external actors can support it, sustainable reconciliation requires an intensive focus at the grassroots – maridhiano mashinani – by faith institutions and local civil society to build relationships of interdependence. He wrote:

Recently, Pace University’s International Disarmament Institute partnered with the Catholic Diocese of Eldoret to develop a follow-up book, Mardhiano Mashinani (Reconciliation at the Grassroots). With co-authors from the Diocese and beyond, Korir explored how reconciliation after violent conflict is a subtle, slow and often difficult process that is not just about ending observable fighting. Drawing on almost 25 years of experience with peacebuilding at the community level, Korir argued that reconciliation requires communities to recognize the worth of others, atone for injustice, heal wounds of the spirit and commit to building a non-violent, equitable and just society. While external actors can support it, sustainable reconciliation requires an intensive focus at the grassroots – maridhiano mashinani – by faith institutions and local civil society to build relationships of interdependence. He wrote:

When Jesus disarmed the Apostle Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane, when he commanded that we love our neighbor as ourselves and turn the other cheek, he challenged us to build a new society rooted in respect and non-violence, rather than the maiming and killing of our rivals. But how do we do this in our context and our time? … [T]here is no panacea, no simple magic solution. … [I]t is not enough to talk to each other. Reconciliation cannot solely be on a personal, one-on-one basis. It requires a concerted effort to reorganize the political, economic, social (and too often religious) systems that produced the violent rupture in relations. … We must commit body, heart, mind and soul to work for justice and social transformation, working in solidarity with those working for structural change at the local, national and global levels.

Maridhiano Mashinani is available as a free e-book here. In Kenya, it is also available in a print version, published by Catholic University of East Africa Press.